How I found all corporate usernames in Iceland

(This article was not written using AI)

One of my favorite methods to gain initial access to companies is finding valid credentials. If your target is just one employee, this might be near impossible. But what if you have hundreds, or even thousands of targets? What if the target victim is anyone in Iceland? Then gaining valid credentials goes from near impossible to near certain.

Ethical disclaimer

This article describes techniques for discovering social security numbers, usernames and testing login resilience for educational purposes only. I performed this work as an ethical security researcher. Do not use these methods to access systems you do not own or have explicit permission to test. If you find a vulnerability, report it responsibly.

1. How to discover the national registry

The first step is to download the national registry. You might think that is not possible because the national registry is not open to just anyone, and you are right, unless you are a hacker. Using the hacker mindset, you set out with the aim of obtaining a copy of the national registry.

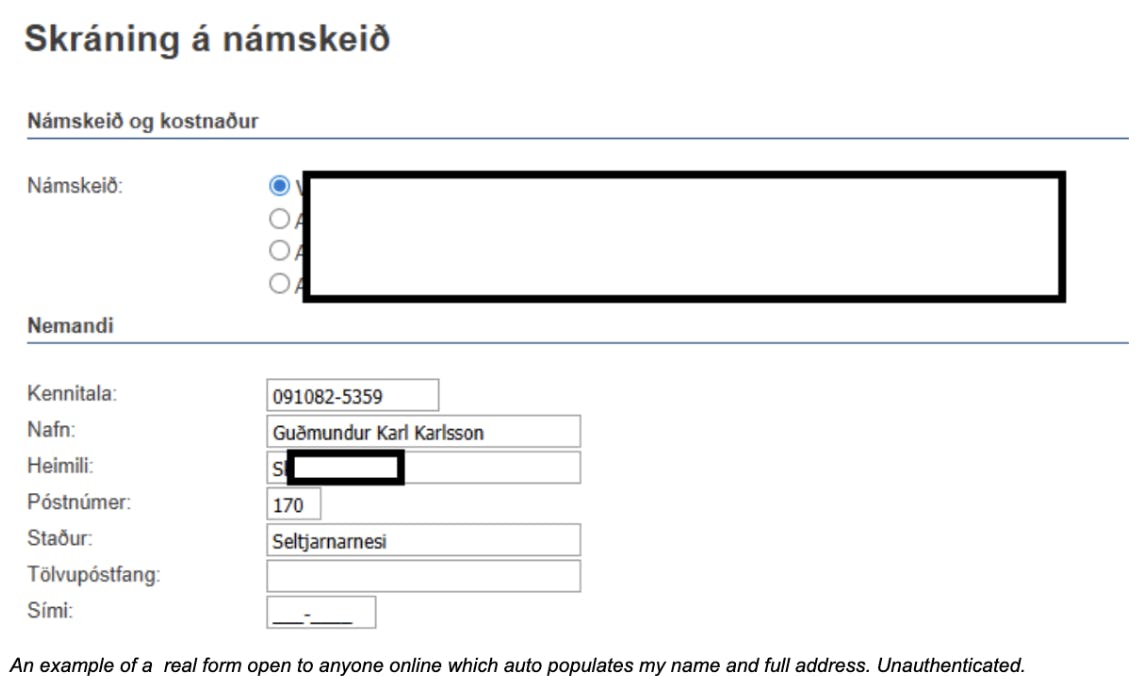

There are a few ways to do that (other than downloading it from your place of work). Most start with locating an endpoint where you can enter a social security number for an individual, and the form you are using automatically displays the person’s full name. Think, for example, when you are transferring money to someone: you input their social security number in the recipient field and their name is automatically added to the name field.

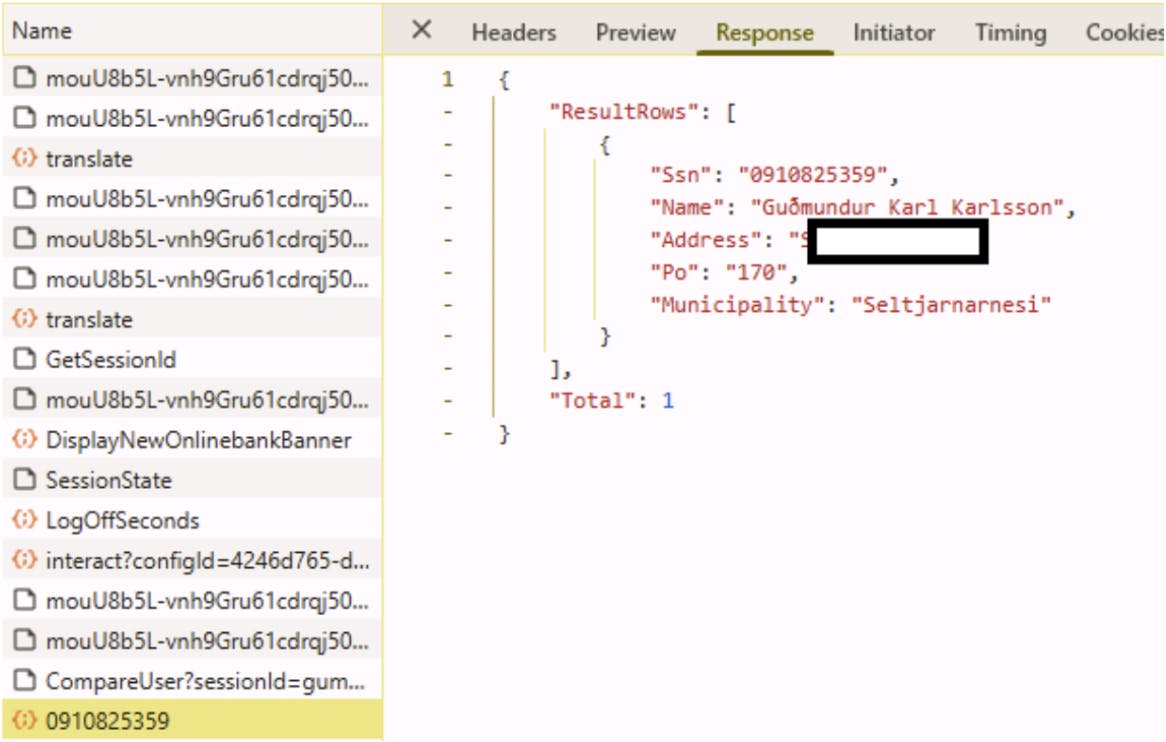

If you proxy the traffic between your browser and the backend service you will probably see the request being sent and the response received. That request is usually not complicated. You can grab that request and try it in a command shell, and the chances are you will get the person’s name, and even full address, in raw JSON format.

I am going to go on a deep dive here, so if you are not interested in the technical details, feel free to skip to the next section. Just know that I can use this traffic to guess everyone’s kennitala and get their full name and, in some cases, home address according to the government, not the phonebook.

Deep dive into obtaining the national registry

On rare occasions you can even find an endpoint that accepts a name and returns a kennitala where you can type in a small subset of characters, for example “a” and you will get everyone that has “a” in their names. Then you can promptly proceed to download the entire national registry by going through the alphabet until you have everyone. That’s about 32 requests unless you include C and Z for good measure.

If you don’t find such a convenient endpoint, but you do find one that will accept any number of requests in quick succession then you can use that too. It’s just a little more work.

Create a script and just send all possible social security numbers in a loop and collect the responses. Easy as that.

This works because of a little quirk in how our social security numbers work. We have this thing called “vartala” which is a mathematical function that will tell you if a kennitala is valid or not. I am not going to go into details on how exactly that works, but, if you reverse engineer it, you can create every single possible kennitalas for all days of every year since the oldest person in Iceland was born. Or just, since 70 years ago to limit the scope to retirement age up until about 20 years ago to exclude young people. This is not complicated, just ask AI. It turns out that the maximum number of kennitalas you can have each day is ~72. Which means that theoretically, you can only have ~72 people in the registry born on the same day. (This is being addressed recently with the introduction of a “system social security number” which supposedly does not need to pass this check. It’s going to be a nightmare because most systems in Iceland implement this check and reject the social security numbers that fail).

This means that if we only want everyone who is of working age, between around 20 and 70, we only need to send 1.314.900 requests to the server to download everyone from the national registry. You might think that is a lot, but remember, we are using computers. Computers do this sort of thing for a living. And these are some of the most optimized endpoints in most systems because looking up someone in the corporate database is one of the most common and crucial tasks in most organizations. Some endpoints can return hundreds of results every second from their up-to-date national registry copy.

It is not a bad idea to use an endpoint that will allow you to remove the cookie and/or authorization header and see if it still works. Use a VPN for good measure, and you are as good as anonymous while you calmly proceed to extract the names and the legal residence of every Icelander dead or alive.

The reason this works is because of how we abuse the social security number system. In most other countries, your social security number is a secret that is not easily guessable. And even if you did, endpoints that will provide you with the person's name and address are even harder to find. Not impossible, but hard. And when they are found, they are classified as a major data breach.

2. Guessing everyone's username

Alright, but how do you get from there to guessing passwords? Companies do not use kennitalas for corporate logins, so all you have now is usernames that are often different from customer identifiers. That is not what we are interested in at the moment. Maybe in my next blog post.

Companies use various combinations of employee names for usernames. For example, my name is Guðmundur Karl Karlsson. My corporate email address is likely one of the following:

gumdundur.karl.karlsson@smelltuher.is

You get the idea. The first thing I do is check if employees are listed on the company website. That makes things a lot easier. Some sites even include emails, and some use “(hja)” instead of “@,” which does not slow me down.

But I am interested in every company in Iceland. Fortunately, most companies have stopped advertising employee details on their site. Now I already know most people’s names in Iceland because I have a copy of the national registry. All I need to do is figure out which username style the company uses for logins.

Often the email is the full name, while the login name is a shorter version. This might be as easy as Googling a couple of employees, and it is almost guaranteed that some people use their login name as their email. In some cases I have gone through document metadata to find “Created by.” The point is, it is easy. I compile a list of every possible email the company might use, using every name from the registry. That gives a few hundred thousand possible email combinations for all working-age people in Iceland.

Enter Microsoft

Again, I am going to go on a bit of a deep dive here and explain exactly how I get the usernames. If you are not interested in the technical aspect, feel free to skip to the next section.

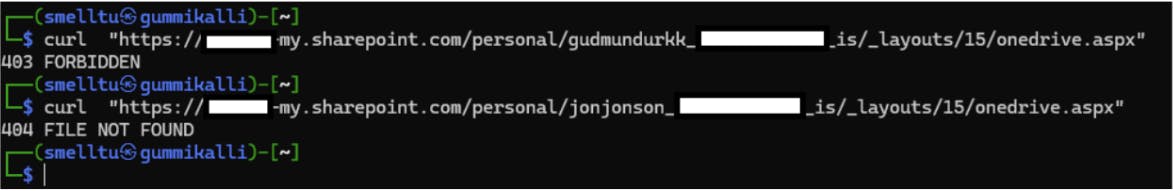

Just know that using what I have so far, I can use a OneDrive feature to get login emails of everyone who works at a company. A common tool in a hacker’s arsenal is a fuzzer. A tool that quickly runs through a list of queries and reports responses including headers and HTTP status codes. OneDrive has an endpoint that accepts a company’s tenant name and a username and returns 403 (access denied) if you try to access an employee’s Documents folder, while it returns 404 if the folder does not exist.

I construct a string with a placeholder for the potential username, then use FFUF to test that string against every potential username. Going relatively slow on a VPN, so I don’t annoy Microsoft or get blocked on my home network, I can enumerate every valid username on the company network in about an hour or two, simply because valid users return 403 while invalid ones return 404.

An example ffuf command I used for this purpose was:

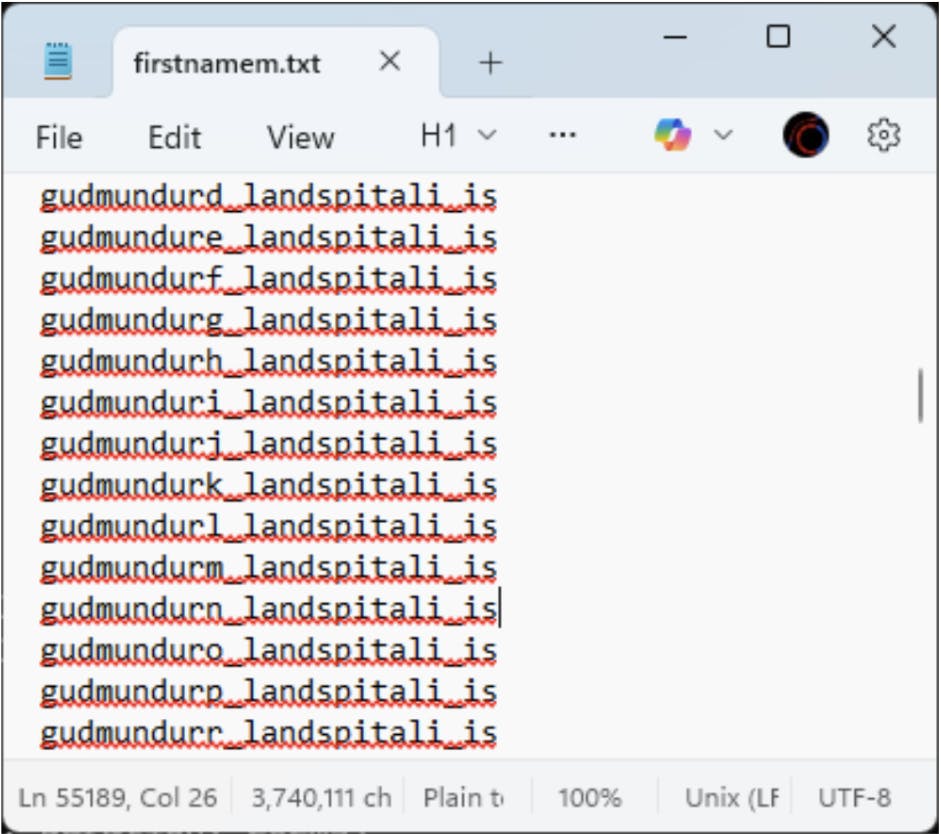

ffuf -w firstnamem.txt -u https://healthis-my.sharepoint.com/personal/FUZZ/_layouts/15/onedrive.aspx -t10 -mc 401,403,200

In this case, firstnamem.txt contains all possible combinations of a person’s first name and middle initial.

3. How do I get the passwords

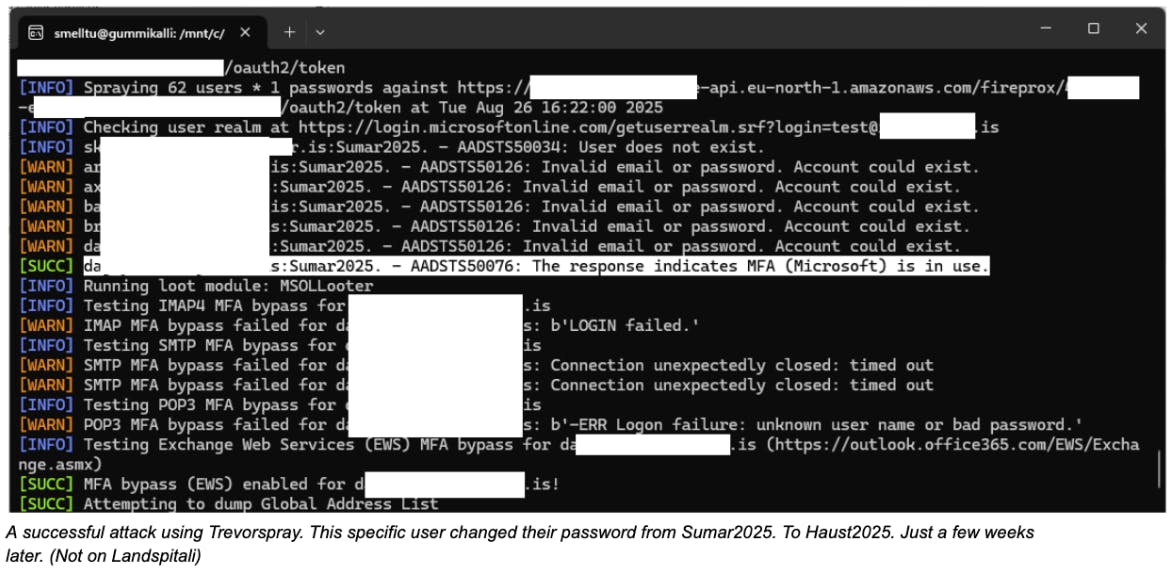

As I mentioned before, I do not need everyone’s password, I just need one. The odds are at least one person is using a weak, predictable password like Sumar2025. I use a tool called trevorspray to systematically test a small number of passwords (usually 5–10, depending on the company’s lockout policy) against many users.

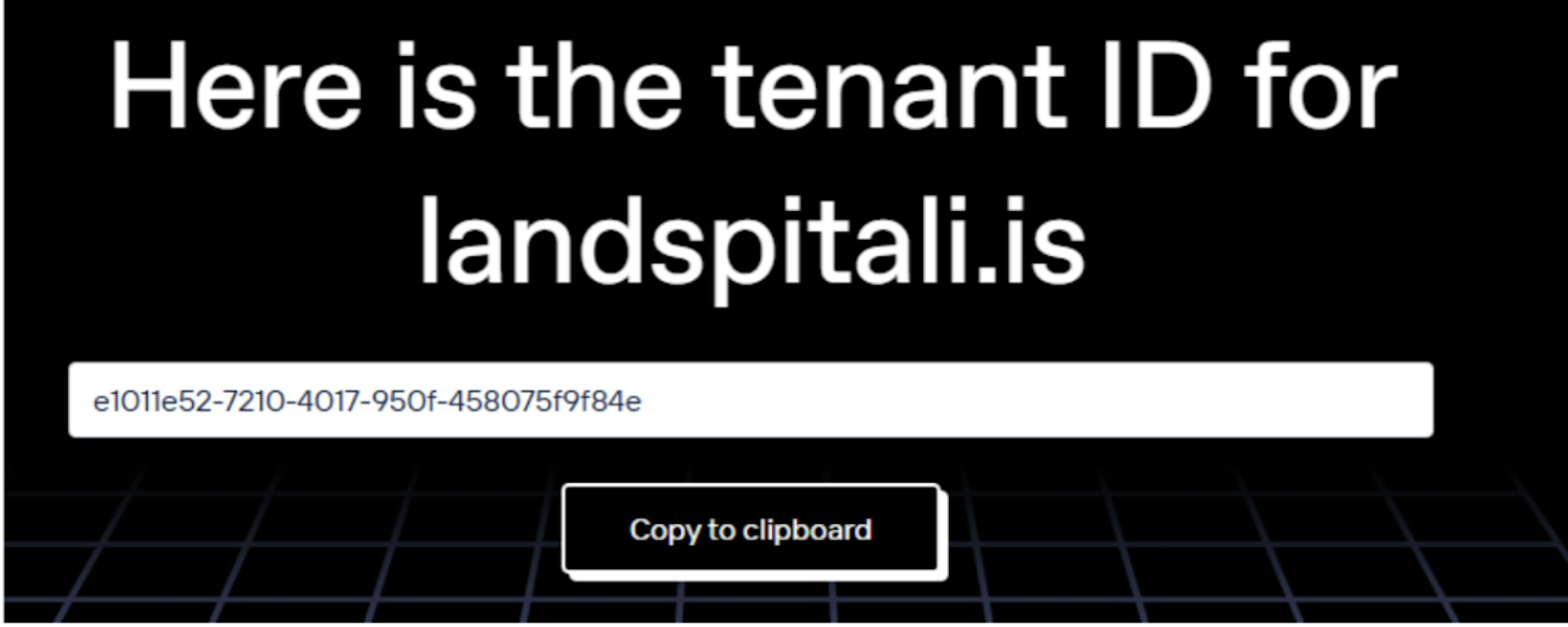

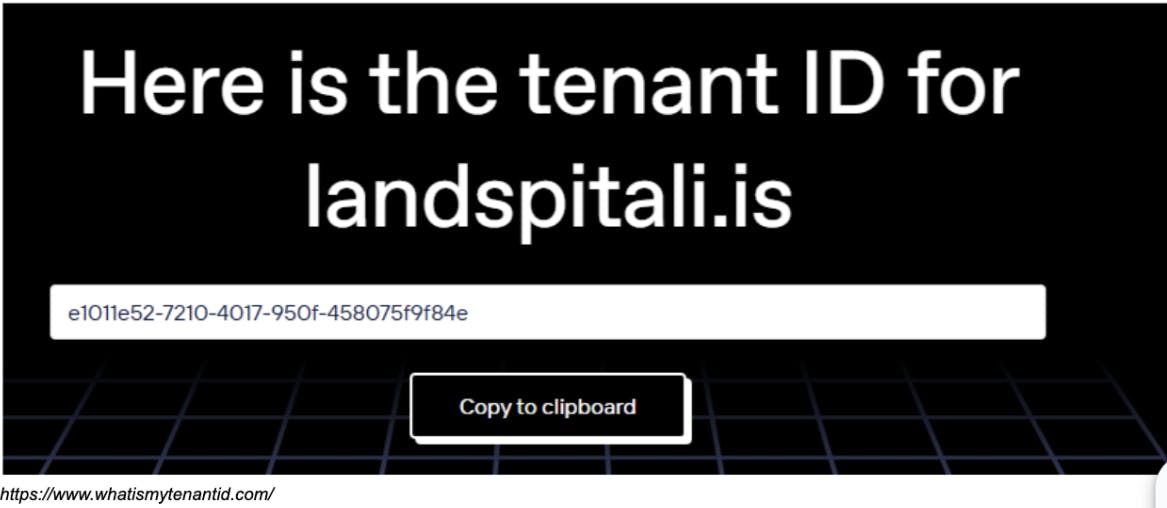

I will not go into deep technical details about how that tool works, because it is documented elsewhere. To avoid getting flagged by Microsoft or a firewall I use an API gateway hosted on Amazon. That makes each request appear to come from a unique IP address, which can bypass naive rate limiters bound to the attacker’s IP address. The gateway forwards requests to the company’s tenant /oauth2/token endpoint using the company’s tenant ID.

I run these procedures seasonally, about four times a year. After 5–10 failed attempts users typically get locked out until they reset their password after a valid login. Many companies implement smart lockout features so the user may not notice, because logins can still succeed from known IPs, the company VPN, or on-site networks.

I leave users 2–3 attempts in my testing because I practice ethical hacking, and I am not trying to cause unnecessary pain. I am trying to get valid credentials so I can find a vulnerable system to exploit and responsibly report to the bug bounty program Defend Iceland, and hopefully receive a small reward for the effort. The odds are, if I were not an ethical hacker, this initial access could be all that stands between a company and a major data breach.

4. How do we protect ourselves

We messed up. We have to start protecting the national registry. We must protect users by securing seemingly innocent endpoints. Such endpoints are now common. You can barely register on a pizza app without the UI looking up your name on the backend using your social security number, which can then be abused to look up a victim’s legal residence.

We owe this to our users and to everyone in Iceland. Corporate networks often depend on these same registries, as I hope I demonstrated in this post. It goes without saying that every application we use must have multi-factor authentication enabled by default. This includes third-party apps for employee timecards, staff union holiday pages, and everything employees, customers, and vendors touch for personal or work reasons.

Most major breaches start with a single user’s compromised credentials. Often that compromise is even easier than what I described, because the credentials usually just come from data breaches published online.